SARAH STEPHENS IS NOT YOUR AI GRANDMA

Some thoughts about digital personalities in my work

(self-indulgent blather about my take on artificial digital beings, as I’ve written them)

I’ve been watching the latest AI developments with a somewhat…oh, what word do I want? Not jaded, not cynical, but definitely somewhere in between. Especially when I start reading about “AI Grandmas” and the use of that tech to speak to long-dead relatives. Oh, it’s presented with that same amber glossiness that seems to dominate the worlds of AI visual creations. But…we’re already seeing some of the dark side of these AI creations with reports of self-harm and worse coming from AI “personalities.”

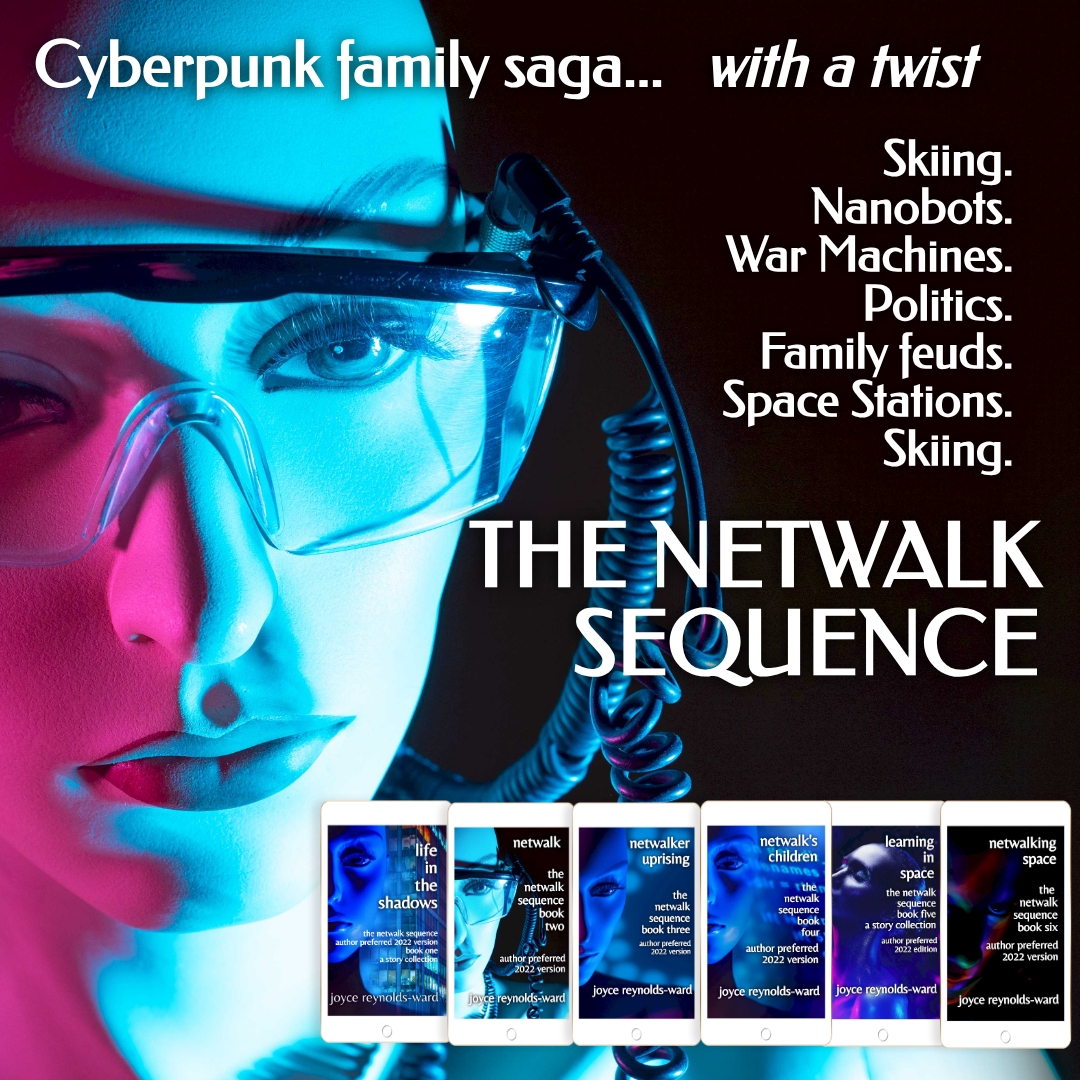

One reason for my attitude is that the creation of self-aware digital personalities is something I’ve somewhat explored in my work, most notably the Netwalk Sequence series and the Martiniere Family Multiverse Saga. In both cases, the tech I explore is already somewhat different from what we are seeing. I don’t go into the nuts and bolts of just how that self-awareness ends up happening (well, a little bit in the Martinieres). But nonetheless, I think this dynamic of what that really looks like is something very much overlooked in the current hype around “preserving the memories of your loved ones” in order to recreate them in a digital simulation. I can oh-so-easily see how it could turn bad.

What happens if AI Grandma is toxic? Or if AI Grandma develops sufficient self-awareness to start meddling in the affairs of her descendants? It’s entirely possible. And while AI Grandma might not have the ability with current tech to really muck up her descendants’ banking and financial history…there’s still a lot of damage she can do to living beings.

The Netwalk Sequence was my first exploration of just what the problems with a separate digital personality creation could end up being. I started building the Netwalk Sequence world back in the ‘90s, when digital personality uploads were somewhat the fashion in fiction and in theory.

My base assumption was that digital personalities could completely upload to the internet upon their death. In that world it’s entirely possible to be a complete personality online, with full body immersion, using the mechanism of a highly sophisticated wireless communication chip implant called Netwalk. Uploading came later, in the midst of a dramatic political struggle where an older leader—Sarah Stephens—uploaded upon her death and began to stalk and attack her opponents. The new development was called Netwalk, and the uploaded personalities called Netwalkers.

A restraint that I created in the Netwalk universe was that Netwalkers would go insane and turn predatory on living beings if completely cut off from sensory inputs. They would attack alive users of Netwalk in order to gain sensory exposures and recharge themselves—as well as fulfilling agendas and settling resentments that hadn’t been dealt with in life. In some cases this would end up as possession of the living being by the Netwalker. As a result, with the exception of a handful of rogues, Netwalkers ended up being tied to a living host, most specifically that host’s Netwalk chip. In the Sequence, we see is how this plays out within one powerful family, the creators and controllers of this technology. With some other dynamics thrown in as well—the control of a war machine of unknown origin which has some influence on the development of the original Netwalk, plus intensely weird family history that involves a lot of infighting and struggles over who controls what.

There’s no grudge like a family grudge, shall we say?

In the Martiniere Multiverse, I postulate something closer to our current concept of the “AI Grandma,” where videos and recordings lead to the creation of digital thought clones. Thought clone appearances in the Martiniere Multiverse aren’t constrained to computers and devices, however, and they can hop universes. This is somewhat connected to a magical Fae origin which is tied to a computer worm that can also skip through assorted multiverses.

The Martiniere digital thought clones (digis for short) differ from Netwalker personality uploads at death in that they are specifically digital constructs of a once-living personality, and only become activated upon specific actions by a living person who is keyed into the algorithm. The digis are fully aware that they are digital constructs and are not the uploaded personality of the dead person they’re modeled after.

Digis don’t appear in every Martiniere book. To follow their development chronologically in series order, start with The Enduring Legacy, the fourth book of the Martiniere Legacy series. We see Gabriel Martiniere’s first awareness of digis shortly before his death, when he ties the appearance of a dangerously destructive computer worm to specific holes in not just his memory but the memories of his closest family. Gabe takes the first steps to establish the bounds of his digi, with a specific activation algorithm tied to certain family members.

More details about digis and their creations happen in two of the Martiniere Legacy standalones, The Heritage of Michael Martiniere and Justine Fixes Everything: Reflections on Mortality. Heritage shows Gabe’s activation; Justine goes into further complications. However, the most details and the most explicit multiversal version appears in the three books of The Cost of Power: Return, Crucible, and Redemption.

Like Netwalkers, digis are capable of possessing living beings and bending them to their will. There are malign digis and beneficial digis. We only see them in the context of one, powerful family because, in both cases, the artificial entities serve as chess pieces in ongoing family battles. They are obstacles that need to be navigated and overcome by the protagonists.

(Sarah Stephens and Philip Martiniere would probably strongly disagree with me but—nothing says that they are pawns.)

Back in real life, Netwalk is probably not at all feasible, though digis…may be. Current technology doesn’t allow for digis to function the way I wrote them in the Martinieres, but some of the same issues raised by both Netwalk and digis still exist. The news has multiple examples of people being influenced by AI interactions to do harm, whether to themselves or others. Or of people who develop a strong emotional attachment to artificial beings to the detriment of their attachments to living beings.

Rather than the apocalyptic stuff I postulated in the Netwalk and Martiniere books, that’s the real harm in uncritical adoption of the creation of artificial beings. At what point do we slip from a clear awareness that “this is a creation; this is not real” to uncritical acceptance of these creations as real beings?

What happens if we start treating these AI creations as something above and beyond an artificial construct?

What rights will they have as opposed to living humans? Or lack of rights?

What happens if they turn malign, either due to the manner in which they are constructed or due to abusive treatment from living humans? Then what?

All food for thought.

Meanwhile, the artificial beings I created in my own worlds are definitely not your happy-happy AI Grandmas. And at times, I wonder if those imperfect visions of mine may end up reflecting an actual reality.

We shall see.